Stories

UN Declaration and Programme of Action for a Culture of Peace

Personalities in the "culture of peace bed"

Probably the greatest achievement of my life has been the drafting of the UN Declaration and Programme of Action, which was adopted by UN General Assembly on September 13, 1999. It is the fundamental document of the culture of peace, and one of the great documents ever produced by the United Nations, on a par with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as it spells out in concrete terms how the United Nations can achieve its original purpose, which is to abolish war. On the 25th anniversary of the resolution, I published a blog describing my involvement in its drafting.

Director-General Mayor asked me to compose the draft programme of action and asked Sema Tanguiane to compose the draft resolution, both of which had been requested by the UN General Assembly. To begin in April 1997 I drafted a memo sent by our unit to the relevant UNESCO sectors, asking for their inputs and I drafted a similar memo sent by the Director-General to other UN agencies. As can be seen from the draft outline of the programme of action in that memo, I had already begun to compose the definition of the culture of peace as the opposite of the principal characteristics of the culture of war.

The final draft of the document (A/53/370) was submitted by UNESCO to the UN on September 2, 1998. Its eight action points were the fundamental principles for the transition from a culture of war to a culture of peace.

Because of opposition from the European Union and its allies, expressed by procedural maneuvering, the Declaration and Programme of Action was almost never even considered by the General Assembly (see Early History of the Culture of Peace).

Eventually, however, the resolution was considered, thanks to the persistent efforts of the countries of the South. Then it went into nine months of informal diplomatic discussions, guided by the Ambassador from Bangladesh, Anwarul Chowdhury. There were 18 informal consultations which I was told the most in the history of the UN. Why? Because of sustained opposition by the European Union, the United States and their allies. At one memorable informal on May 6, 1999, the German representative on behalf of the EU insisted that no mention should be made of "culture of war" because "there is no culture of war and violence in the world." As a result, all mention of the culture of war was removed from the text of the resolution, thus making it difficult for readers to understand the underlying rationale. The EU and the United States objected to reference to the "human right to peace" with the US delegate saying that "peace should not be elevated to the category of human right, otherwise it will be very difficult to start a war."

Many compromises were made, including a very important concession by which the possibility of a voluntary fund to support activities for a culture of peace, was removed from the resolution. As a result, in the succeeding years, the UN secretariat has had no budget and no actions for the culture of peace.

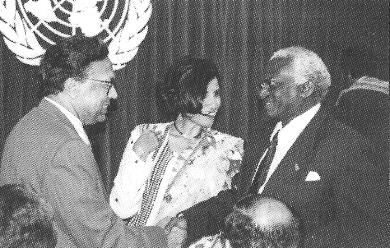

Anwarul Chowdhury at left, with Nina Sibal and Archbishop Tutu at the UN

Despite the compromises, thanks to the tireless efforts of Anwarul Chowdhury and his diplomatic colleagues from the South, as well as Nina Sibal (from India) and Anita Amorim (from Brazil) at the UNESCO Office in New York, the main lines of the culture of peace were retained in the final programme of action.

September 13, 1999, was the last day of the 53rd Session of the General Assembly. If the Declaration and Programme of Action had not been adopted on that day, the last day of the session, according to the rules of the UN, it could not have been introduced again in another session, but would have been killed and buried.

What happened behind the scenes on September 13, 1999, that made possible the adoption of the resolution? I have always assumed that those who were opposed (the Europeans, Americans, Japanese, Canadians, Australians, etc.) were confronted with the choice of adopting the resolution by consensus or submitting to a roll-call vote in which case the South would have had enough votes to over-ride any opposition by the North. However, this is the kind of information that UN diplomats keep to themselves, so we may never know exactly how it happened.

As has been the case for Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we may expect that the Declaration and Programme of Action on a Culture of Peace will continue to gain importance as a fundamental, universal document over the years, as it is used in the struggle for the transition from a culture of war and violence to a culture of peace and non-violence. As stated by Anwarul Chowdhury to the General Assembly on September 13, 1999:

I believe that this document is unique in more than one way. It is a universal document in the real sense, transcending boundaries, cultures, societies and nations. Unlike many other General Assembly documents, this document is action-oriented and encourages actions at all levels, be they at the level of the individual, the community, the nation or the region, or at the global and intellectual levels ... This document really goes ahead in terms of bringing in various subjects that the Assembly has rarely touched in its 50 years of existence.

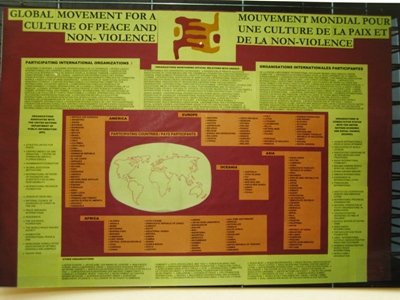

Of particular importance for all of the work that I have done since was the call for "a global movement for a culture of peace" in the Programme of Action on a Culture of Peace, the first time the UN ever called for a "movement":

6. Partnerships between and among the various actors as set out in the Declaration should be encouraged and strengthened for a global movement for a culture of peace.The "civil society . . . at the local, regional and national levels" was indicated, along with UNESCO, the UN and the Member States as one of the actors.

7. A culture of peace could be promoted through sharing of information among actors on their initiatives in this regard.

Poster for the Global Movement made by the IYCP team for the exhibition of

the General Conference in 2000, based on participation

by the civil society in the Manifesto 2000 mobilization.

|

Stages

1986-1992

Fall of Soviet Empire

1992-1997

UNESCO Culture of Peace Programme