Stories

In 1966 I began work on my dissertation at Yale. Although it was technically in the Department of Psychology, I worked under Professor John Flynn of Yale Medical School who, at this time, shifted his affiliation from the Department of Physiology to the Department of Psychiatry.

Also in 1966, I married my classmate at Yale, Nina Relin, who was also beginning work on her Ph.D., although she was working under a different professor. The two of us, along with a third student who was her boyfriend at the time, had taken a course in sensory processes where I had proposed a model for the study of complex behavior.

Nina and I set up adjoining laboratories, and each of us began work using single neuron recording from the brain. Following the model that I had proposed above, I was looking for cells in the hypothalamus or midbrain central gray related to fighting behavior in cats. Nina was looking for cells related to visual perception in the visual cortex. Each of us used cats from the Yale Medical School animal facility.

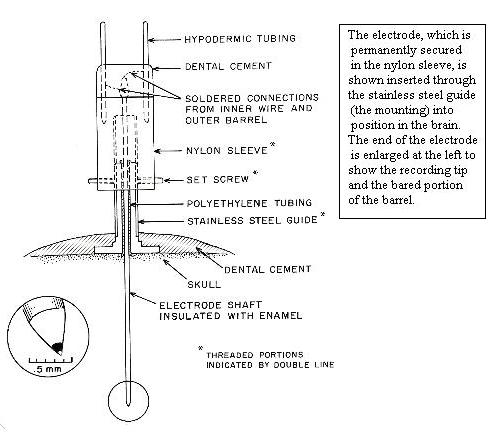

Because single neuron recording was a relatively new technique, we were each working more or less on our own, with little help from our professors. This was particularly pronounced in my case because I was working in the shop with milling machines and microscopic assembly for days on end inventing a new kind of electrode that would enable me to record from brain cells during violent movement. This was something that had never been done before, and has rarely been accomplished in the almost half century since.

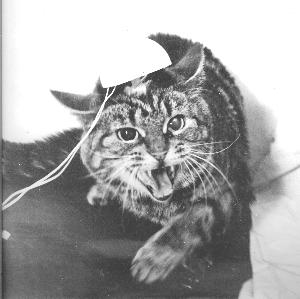

Over the course of the ensuing year, I succeeded brilliantly with my newly-invented electrode and was able to record from neurons in the central gray that fired if and only if the cat was fighting back against a second brain-stimulated cat (see photo below). But Nina could not get her electrodes to work, and, though I tried, I was not able to help. She fell into a depression and stopped working.

The contradiction was painful. We continued to live together, but I was not able to celebrate my success, and increasingly, she was not able to discuss anything having to do with laboratories or degrees. Finally, in 1967, we left it all behind and went to Italy for a year where I had a post-doctoral fellowship, and Nina found work teaching English to, among others, the conductor Claudio Abbado, and found enjoyment going to the opera at La Scala.

Looking back on it, I regret that I could not celebrate my dissertation. Late into the night, working with my cats, I would listen to the loudspeaker broadcast of neurons as the electrode penetrated into the brain of the "recording cat" and as I opened the partition separating the two animals, stimulating the "attack cat" so that they would start fighting.

I had a special relationship with those cats from whom I could record on many occasions. Some of them would follow me down the hall in the medical school rather than being carried in a box. Once, however, this backfired, as the cat escaped and ran down a staircase and out into a sub-basement that extended under the entire medical area. I set a trap for him and caught him, but in trying to take him from the trap, I was badly bitten and he escaped. He was wearing the first electrode that had worked properly and it took me several months to be able to make another that worked as well!

|

Cat attacking as result of brain stimulation. This photo was sent to Science magazine in the hopes that it would be used for the cover of the issue in which they published a brief account of my dissertation research, but it was not used. |

There is something amazing listening to the "sounds" made by neurons in the brain when their impulses are amplified and you can listen to them by loudspeaker or headphones. I had made recordings in 1967, but now years later they are lost. As I recall, sometimes they are like ocean waves of dozens, hundreds, thousands of cells in chorus. Sometimes you can isolate and listen to one neuron through various procedures, trying to understand its "behavior." Cells from the reticular formation would respond to anything. Heading for the central gray I would pass through the superior colliculus and layers of cells that responded to visual stimulation. In the central gray I found those precious few that fired if and only if the cat was fighting. Once in a while, a cell would die as the electrode penetrated into it, and the sound was a rising tone, ending in a virtual scream and then trailing off once more into the silence of death. A window into another world!

I cannot do better than quote the description of brain cells by that grand old neurophysiologist Sherrington from his book, Man on His Nature:

Suppose we choose the hour of deep sleep. Then only in some sparse and out of the way places are nodes flashing and trains of light-points running. Such places indicate local activity still in progress. At one such place we can watch the behaviour of a group of lights perhaps a myriad strong. They are pursuing a mystic and recurrent manoeuvre as if of some incantational dance. They are superintending the beating of the heart and the state of the arteries so that while we sleep the circulation of the blood is what it should be. The great knotted headpiece of the whole sleeping system lies for the most part dark, and quite especially so the roof- brain. Occasionally at places in it lighted points flash or move but soon subside. Such lighted points and moving trains of light are mainly far in the outskirts, and wink slowly and travel slowly. At intervals even a gush of sparks wells up and sends a train down the spinal cord, only to fail to arouse it. Where however the stalk joins the headpiece, there goes forward in a limited field a remarkable display. A dense constellation of some thousands of nodal points burst out every few seconds into a short phase of rhythmical flashing. At first a few lights, then more, increasing in rate and number with a deliberate crescendo to a climax, then to decline and die away. After due pause the efflorescence is repeated. With each such rhythmic outburst goes a discharge of trains of travelling lights along the stalk and out of it altogether into a number of nerve branches. What is this doing? It manages the taking of our breath the while we sleep.

Swiftly the head-mass becomes an enchanted loom where millions of flashing shuttles weave a dissolving pattern, always a meaningful pattern though never an abiding one; a shifting harmony of subatterns. Now as the waking body rouses, subpatterns of this great harmony of activity stretch down into the unlit tracks of the stalk-piece of the scheme. Strings of flashing and travelling sparks engage the lengths of it. This means that the body is up and rises to meet its waking day.

|

Stages

1986-1992

Fall of Soviet Empire

1992-1997

UNESCO Culture of Peace Programme