Stories

The physiology of Nickolai Bernstein

Evolution of

the brain

and social behavior

Learning languages

* * *

|

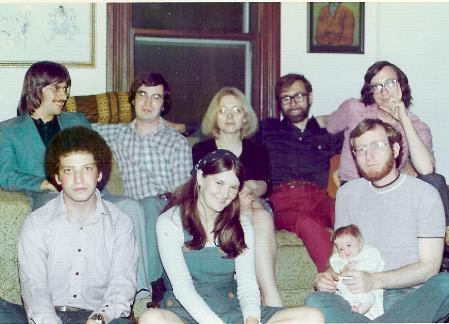

At Yale University, after my Ph.D. and three post-doc years, I was offered an assistant professorship of anatomy with "soft money." In other words, Yale would not pay me, but would expect me to get grants to pay my own salary and expenses, with a healthy overhead payment to Yale. It was a good deal for them, but not for me. And besides, the animal care department at Yale informed me that I would need a half million dollars if I wanted to equip outdoor pens to observe natural cat behavior. Hence, in 1970, when offered a "hard money" professorship at nearby Wesleyan University, I jumped at the chance and said "yes." But how could I carry out my research on the brain mechanisms of aggression with a low budget? At the dinner table one evening with Nina at our house, I posed the question to our two neurophysiologist friends, David Egger and Ted Coons, who had come for dinner. Their answer was simple: work with rats instead of cats. I had done my Ph.D. thesis working with cats at Yale, and again with cats in Milano, although I shifted to rats as a postdoc under David Egger. Thus, I established the "ratlab" at Wesleyan's psychology department, taking over the entire fifth (penthouse) floor. I used to say that I ran an efficient lab with ratfood and students coming in one door, and first-rate scientific publications and ratshit going out the other door. Indeed, from 1970 to 1992 when I left definitively for UNESCO and the culture of peace, we put out almost a hundred major scientific publications, most dedicated to the brain mechanisms of aggression. Most of the work was done with my students, but within a couple of years, I was joined on the Wesleyan faculty by Harry Sinnamon who set up an adjoining "ratlab" on the fourth floor and we often worked together, sharing students, ideas, even hiking and camping trips, including memorable several-day trips in the Adirondacks canoeing on one occasion and hiking across all the high peaks on another. For several years, Harry and I also worked with a post-doc, Fred Pond.

The students learned how to do scientific experiments, and together we kept many volumes of reports, written in scientific format, which, after my retirement, I provided to my archives at the Wesleyan library. Many of the students went on to distinguished careers in various scientific disciplines. These were very enjoyable years, as there was a good feeling of teamwork in the laboratory, and a confidence in the positive contribution of scientific research to human progress, in particular the idea that knowledge of the brain mechanisms of aggression could help us avoid World War III. At first I played the "grantsmanship game" which was usual for scientists and obtained a large government grant from NIH under which I bought equipment and hired a previous colleague of Harry Sinnamon, Fred Pond, to work with us in the laboratory. But I found the grantsmanship game to be very corrupt. Scientists would serve on the NIH review teams in order to further their own career and block the careers of other scientists whom they considered as "competitors." After all, there was only a certain amount of grant funds available and the more others received, the less you received. Once, such a review team visited my lab and asked such insulting and provacative questions that I could not stand it. I said simply, "that is a stupid question." The chief of the review team closed his book ostentatiously and said, "it is evident that you don't want a grant from us." Later, the one member of the grant review team that had real integrity told me privately that I was right and that he admired me for it. I could afford to leave the grantsmanship game because of generous support from the University which paid for a part time animal caretaker and feed for the animals. As for scientific instruments, I simply paid for the materials out of pocket and built everything myself. I recall the time that I needed electronic counters for an experiment in which the variable to be measured was the number of revolutions of wheels on which the rats were running. Counters from medical supply houses would cost $800 each and I needed five. Instead I bought five hand-held calculators for $5 each and hot-wired them so that each time the relay was closed it simply added one. Over the years from 1971 to 1993, my students and I developed the most advanced model of the brain mechanisms of aggressive behavior. As many as a hundred students contributed to the research, and a number of them published as co-authors with me, including not only Michael Lehman, but also Jon Mink, John Kanki, John Zook, Michael Edwards, Will Boudreau, Chris Cowan, Cathy Kokonowski, Karl Oberteuffer, Kaleb Yohay, Sun-Hi Lee, Walter Severini, Mary Ellen Marshall, Jennifer Stark and Judy Mitchell. A number of the students have gone on to distinguished medical and scientific careers. My confidence in my scientific career eroded in the 1980's when I began to study and recognize the positive role of aggression in the psychology of peace activists, but it was already shaken at the end of the 1970's by an incident involving single gene effects on aggressive behavior, but that is another story. |

|

Stages

1986-1992

Fall of Soviet Empire

1992-1997

UNESCO Culture of Peace Programme