Stories

The physiology of Nickolai Bernstein

Evolution of

the brain

and social behavior

Learning languages

* * *

When I started teaching at Wesleyan in 1970, I insisted on small classes where the students could sit in a circle rather than all facing me, and I tried to listen to the students and model how I expected them to learn to listen to each other and work together. When I first arrived, however, I was required to teach introductory psychology which always had big enrollments. I asked for a classroom that would hold only 30 students and the first day over one hundred arrived and could not get into the room. I took them all out to the bleachers on the nearby football field and said that we would meet there regularly, so they should bring umbrellas in case of rain. At the next class only 30 showed up in the bleachers so I marched them back inside and starte the course in earnest. Soon after, I met Colin Campbell, the University President, who had a good sense of humor. Instead of reprimanding me, he laughed and said it was a novel way to limit class size.

Profiting from my experience with the revolutionary student movement in Italy, in my laboratory course I required the students to work together in a series of teams doing research at a level of excellence that could lead to scientific publications. The grade I gave them was the average of the grades made by each of their teams rather than individual grades. That meant that to do well they had to help their other team members to do well. Only once in twenty years of teaching did a student refuse to work on that basis.

Like many a new university professor, I set out to teach in order to learn. I chose courses that would enable me to study the topics that most fascinated me, which, at the time, were the evolution of the brain and the evolution of social behavior. For 25 years I taught courses with these titles, as well as a laboratory course devoted to research on the brain mechanisms of aggression.

|

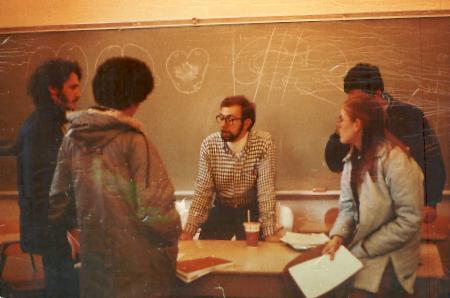

| With students in class on evolution of the brain |

Along the way, I met and worked with many wonderful students, who taught me as much as I taught them. Increasingly, I required the students to do extensive library research and write a term paper on a topic relevant to these courses. I worked out a system, whereby they would be graded at a number of points along the line: for the original proposal, for the results of a literature search, for the first draft of their paper. By the time the final draft was submitted, most of the grade had already been determined, and I had been able to interact with the student along the way. And most important, these term papers were often remarkably good, a learning experience for me as well as for the students (see for example Mike Solomon's thesis).

For more than 15 years I sent out an annual Christmas letter to those who had taken part in my courses (filed with my correspondance), and I have been able to keep up with a number of my ex-students who have established careers in related fields. Unfortunately, I lost touch with several who taught me more than I taught them. One of them was Stanley Benally, a Navajo who was an excellent pre-med student in my lab, but who could no longer engage in surgery, and had to leave Wesleyan, as described in his letter that I still treasure.

After twenty years of teaching I had gained a unique understanding of these fields that was not available in any existing textboooks. I thought about writing such textbooks, but by then, my interests were shifting (the closest I came to writing such textbooks were the lectures I gave in Soviet Georgia in 1980 which were written out and are stored with my publications). My heart was in another course that I began teaching during the 1980's, the psychology of war and peace. Using the same teamwork approach that I had developed in the laborary, the students took part in team projects including the organization of student conferences on peace and sustainable development.

But this, too, was not enough. The more I taught and wrote in this field, the more I realized that the challenge was not just to write about the subject, but to do something about it. This led me to the United Nations and to abandon my career in teaching for a career at the UN.

After my career at the UN, I tried to return to teaching, but it was not very successful. In 2002 I taught a course on the psychology of war and peace at Wesleyan. Out of 30 some students in the class 5 or 6 really connected to what I was doing, but the rest were either uninterested or disappointed that I did not provide them with some kind of knowledge that would further their careers. And, after all, there was no promise of a career of working for peace, since there was (and still isn't) any financial support for young people who wish to work for peace.

On the other hand, the few students who did connect with the course, like Joe Yannielli, Charlie McNally and Ben Oppenheim became the nucleus of the new Culture of Peace News Network, and I have remained in touch with them in succeeding years.

|

Stages

1986-1992

Fall of Soviet Empire

1992-1997

UNESCO Culture of Peace Programme