Stories

Psychology for Revolutionaries

Psychology for Peace Activists

Why there are so few women warriors

The Seville Statement on Violence

A theory of mental illness

* * *

In the height of the Cold War, with the US and Soviet Union ready to launch a nuclear war, the initial idea came from Alan Thomson, the Director of the National Council for American-Soviet Friendship (NCASF), in his discussion with his Soviet counterparts: a People's Peace Treaty.

Alan convened a meeting on May 28, 1985 at the Church Center across from the UN, to which I was invited since I worked closely with Alan in the NCASF. In addition to the two of us, there was Ruth Sillman of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, Ellen Mass of the Cambridge Sister City Project, Howard Frazier of Promoting Enduring Peace, Robert Schwartz of SANE, John Dow of Americans Against Nuclear War, Tony Watkins of the US Peace Council, Ed Rothberg of Ads for Peace, Phil Oke of the Christian Peace Conference and Celia Fink of Women Strike for Peace. We agreed to gather support for the project and established ourselves as the Ad Hoc Committee for the People's Peace Treaty.

Alan Thomson (standing) in 1985 with the Ad Hoc Committee for a People's Peace Treaty. Click on photo to enlarge.

At the first meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee, on June 5, I proposed that "the project may include exchanges of petitions between local organizations, schools, trade unions, churches, city councils, amateur groups." I suggested that this would pave the way for followup work by which organizations would sponsor trips to visit their counterparts in the other country.

During the rest of 1985 and early 1986, I attended a number of meetings of the Ad Hoc Committee and was instrumental in working with Howard Frazier and Lou Friedman of Promoting Enduring Peace to link our project with one that they were organizing: a trip for Soviet and American Peace Activists down the Mississippi River. I also restarted my correspondence with Nobel Laureate Bernard Lown and through him engaged the Physicians for Social Responsibility in the campaign.

I also took responsibility to develop a model participation in the project in New Haven, where my friend Tom Holahan was on the Board of Alderman. Tom convinced the Board to formally endorse the project. We then organized schools, churches and other organizations throughout New Haven to support the Appeal and, on that basis, we prepared a beautiful manual, of which I still have copies, which we circulated throughout the US for participation by cities. Tom became one of the 26 original US and Soviet signatories (see the final, signed copy). Later, in 1990, Tom and I wrote a short article together for the short-lived Bulletin of Municipal Foreign Policy.

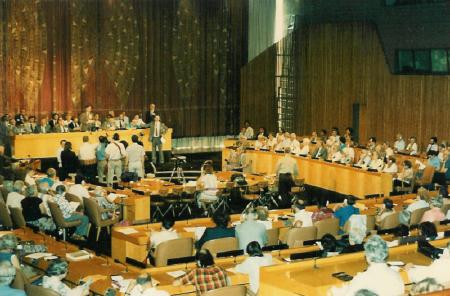

On August 8, 1986, the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, the final version of the document, as amended by the Soviet and American participants on the Mississippi River Cruise and called an "Appeal" rather than a "Treaty", was signed in a ceremony at the ECOSOC chamber of the United Nations (photo below). There were 300 people at the event, and Robin Ludwig, from the Secretariat of the International Year of Peace (1986) commented that "the public was really doing what the UN was established to do: make peace." We held a press conference at the UN Press Room, but got very little press coverage for the event in the United States (I don't know about overseas press). While the Mississippi Peace Cruise was covered by an extensive article in Time Magazine thanks to the work of Lou Friedman, the article did not mention of the Peoples Peace Appeal.

Ceremonial signature of Appeal in UN ECOSOC chamber

In addition to the Appeal itself, a program of cooperation was signed on August 8 between the US Campaign for a People's Peace Treaty and the Soviet Peace Committee formalizing my idea of a people's exchange on the basis of the Appeal:

In order to fulfill the potential of the PEOPLE'S APPEAL FOR PEACE (pending adoption by the Soviet Peace Committee), we pledge our respective organizations to the task of publicizing and disseminating the APPEAL to the peoples of our countries, including gathering of large numbers of signatures, and the exchange of copies of the APPEAL with signatures between local organizations such as city and town councils, trade unioni locals, church congregations, schools. The coordination of all such exchanges will be done by our two organizations. The purpose of such exchange shall be to increase the people-to-people contact between our two countries on the basis of participation in such local organizations and on the basis of the principles stated in the APPEAL.

Then began the hard work of gathering signatures. We hired Mike Quinn from the Catholic Worker, a delightful and energetic young man, to run the campaign. At Wesleyan my students gathered 1100 signatures which we sent to the world conference for the International Year of Peace in Copenhagen. My notes from our Steering Committee meeting of September 13 list mailings of the petition to 32 cities in 19 states. I developed materials for grant requests and worked hard, without success, to obtain foundation support.

In December I took the Appeal to a national meeting of the Nuclear Freeze in Chicago, but we did not get their endorsement. Here are my notes returning home on the plane:

We lost PPA. And it was my fault. I hate to make such a mistake. "It won't be your last," says Al Marder, gently and kindly. But Mike Quinn, Anita Holland-Moritz and Randy, who worked with me all agreed that if we had left the Appeal as a resolution it would have passed easily. By moving it into the tactical amendments, we lost by a vote of 75-45. But it wasn't the only thing that suffered; all tactical amendments were defeated while all resolutions were passed. Of course, we did get about 100 names of local contacts from all over the country with whom we can now work.

In January 1987, Alan went to Moscow to work with the Soviet Peace Committee for a week, including the establishment of organizational pairings. He quoted Slava Sluzhivov of the Soviet Peace Committee that "This is not the Stockholm Peace Appeal. What matters is not the number of signatures, but the number of exchanges." In February, my friend Al Marder from New Haven undertook the task of national organizer for the campaign. Also in February, we announced in our campaign update that a series of Soviet delegations would visit the US bringing signed Appeals and establishing people-to-people exchanges on that basis. The Gray Panthers had pledged to gather a million signatures, and pairings were beginning to be made between churches and unions. I announced that we had requests from 50 high schools in Connecticut to pair with Soviet high schools, and that the Superintendent of Schools of New Haven had mobilized all school principles in the city to gather student signatures.

The campaign advanced well in early 1987. As of our May 6 meeting, we had 55,000 signatures, of which 15,000 came from the Gray Panthers, and 50 pairing requests, including 24 churches and religious communities. By June the organizational endorsement list ran to 4 single-spaced pages.

Meanwhile the FBI did not sit still. After we obtained the sponsorship of Senator Simon from Illinois, he was visited by the FBI and he withdrew his support. And we obtained a memo circulated by the FBI saying that this was the most dangerous initiative in the country! The FBI memo is not public, but similar info is contained in a memo from the US State Department that is available online and excerpted here. Later, we would learn that the FBI had already assigned agents to entrap Alan Thomson to try to stymie the project.

Despite the FBI opposition, we added more and more organizational sponsors who circulated the Appeal for signatures. In the Soviet Union, we were told that 15 million signatures were collected in the first year. In the United States, we accumulated boxes and boxes of copies with rows of signatures below the text of the Appeal, mounting by September 1987 to 380,000 signatures in the US, and by May of 1988 to 500,000.

But something else was going wrong by mid-1987. In May I went to a meeting in Moscow sponsored by our partners, the Soviet Peace Committee, as a dialogue with the Western peace movement. I expected to find enthusiasm for the Peoples Peace Appeal, but found only silence instead. Finally, I literally "cornered" Slava Sluzhivov of the Soviet Peace Committee and demanded to know what was happening. He was evasive and hinted that there were serious matters that he could not discuss. Only later would I learn that already the Soviet Union was beginning to disintegrate.

Al Marder returned from a trip to meet with our partners in the Soviet Peace Committee in Moscow July 13-17, 1987, reporting that the project was still moving forward, saying that our Soviet partners "viewed the joint efforts as most meaningful, holding great promise in developing long-term relationships on the grass-roots level. We agreed that the pairing process ... would destroy the myths, the stereotypes, the preconceived notions we hold of each other. You and we are in a truly historic campaign, a first of its kind in the relations of the peoples of our two countries. We bear tremendous responsibility for the peace of our planet, in this, the nuclear age."

But a month later, the Steering Committee minutes reported "The Peace Committee has not yet responded to inquiries about pairings." By May 11, 1988, still having no response, we wrote to the Soviet Peace Committee:

"Unfortunately, despite our joint written protocol with you for such pairing and our many letters to the Soviet Peace Committee, we have received no concrete follow-up. This has proved very embarrassing to us since we informed the organizations that agreement had been reached and they would be contacted by a similar Soviet organization ... Unless we receive a positive reply in the next two months carrying with it initial steps which we can bring the US groups requesting pairing, we will propose dissolution of the US People's Appeal for Peace Campaign."

In the summer of 1988 Alan Thomson and Al Marder received a verbal understanding from Slava Sluzhivov that the project was still supported, and would be taken up at an up-coming meeting of the Soviet Peace Committee. Again we waited for positive news. And again it did not come. On May 15, 1989, as acting coordinator of the Campaign (Al Marder had quit), I wrote to the Steering Committee and all groups requesting pairing that we were dissolving the campaign. Howard Frazier had returned in April from Moscow where Slava Sluzhivov informed him that it was no longer possible for the Soviets to carry out their side of the campaign. A particularly painful moment for me came when Alan and I took scores of heavy cardboard boxes containing the 500,000 American signatures on the People's Peace Appeal and dumped them in the trash.

Meanwhile the FBI was "killing the horse that was already dead." Alan Thomson was arrested by them on February 7, 1989 in a "sting" operation, by which an undercover FBI agent (an attractive woman) had assisted Alan to deposit $17,000 in a bank in Buffalo, New York, said to be funds from the Soviet Union. This confirmed what I had always suspected, that the series of attractive young women sent to take jobs as assistants to Alan, a bachelor, had been FBI undercover agents with the task of not only spying, but also seducing Alan and catching him in some illegal activity. Alan's case dragged on for several years, and then with the total collapse of the Soviet empire, it was quietly dropped. The horse was dead.

With the collapse of the Soviet empire, it was not only the People's Peace Appeal that died for me. So did the National Council for American-Soviet Friendship and the Connecticuat Association for American-Soviet Friendship which I had led over the years. And the Communist Party USA was split in half at their 1991 convention.

Looking back over the years, I realize that we helped to ensure a peaceful transition during the collapse of the Soviet Empire, and to avoid what was a great danger of nuclear war. But at the time, the experience was painful for me.

|

Stages

1986-1992

Fall of Soviet Empire

1992-1997

UNESCO Culture of Peace Programme