Stories

The brain mechanisms of aggression

Motivational systems of social behavior

International Society for Research on Aggression

Behavior Genetics Association Ethics Committee

The World Wide

Runners Club

for Peace

United Nations University for Peace

Charlie Robbins, barefoot runner

* * *

I had helped set up a single-neuron recording lab, which we called "David's Collective Number 1" for Professor Tengiz Oniani at the Physiology Institute of Georgia for several weeks in 1976, and greatly enjoyed my first encounter with Georgian culture. It is one of the great ancient cultures of the world, including many of the myths and tales that were told by the Greeks, such as Prometheus and Jason. The Georgians insist that they invented not only wine but also the word for it, "ghvino".

Jason Badridze, who had once been the best student of Tengiz Oniani, and whom I had met in 1973, was not around much in 1976 as he had decided to go and live with the wolves to learn their behavior first hand. His wife had kicked him out when he tried to raise lion or tiger pups (I forget which) at the house. But I did meet Jason's young 14-year old protege at the time whose name was Zurab Zhvania.

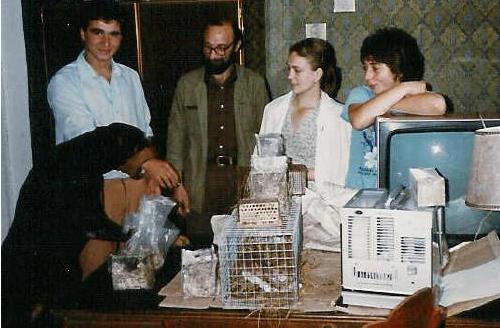

When I came back to Georgia to teach for a semester at the University in 1980, Jason was living in the old section of Tbilisi with a new wife and Zura was now 18. Zura and a group of his friends became "David's Collective Number 2" and they undertook experiments with rats and other muroid rodents, concentrating on how they learned to build their underground tunnel systems.

Zura, at left, with Jason Badridze and Masha and Tamrika Roitbak of "David's Collective Number 2"

There were many amusing stories around "David's Collective Number 2" such as the time that Zura was coming back to Tbilisi on an Aeroflot plane from Moscow when the box of exotic rats that he was bringing to study got open and the rats ran under everyone's feet on the plane!

I prepared and wrote out for the University to keep two lecture series, one on evolution of the brain and one on evolution of social behavior, which is the most complete lectures I have ever done in my teaching on these subjects. The notes are still on file in my office. I would have preferred to deliver the lectures in Russian so that the many exchange students at the University could come, but my Georgian hosts said no. I was told they did not want their girls in the same classrooms as these foreign male students. So I gave the lectures in English with Georgian interpretation!

At this time I took a memorable trip up into the Caucasus mountains with Tengiz Oniani to his family home in the fabled village of Svanetia with its ancient stone towers for defense. This is the part of the world where many people live to be over a hundred years old. Tengiz laughed when I asked him about this. "Sometimes it's exaggerated," he said, "but then it's true that there were over a thousand descendents at my grandfather's funeral!" An especially remarkable tradition of the Georgians is their "gosteprienstva" (this is the Russian word and I have forgotten the Georgian) or their custom of extraordinary hospitality. As Tengiz explained, as long as your enemy is a guest in your house, you must treat him royally, but when he leaves, as he steps across the border of your property, you may shoot him dead. In fact, it was not uncommon to go to a restaurant with a group of Georgians and to find when it came time to pay the bill that the Georgians at another table had already paid for us!

The Georgians love good wines and cognacs, feasting and the tradition of the "tamada" toastmaster. I became rather adept as a tamada, although I spoke more Russian than Georgian, and could not make it to the proverbial 100 toasts. One I recall was for the host: "May you live to be almost 100 years but not quite. May your death be natural but not quite. And may it be at the hands of a woman!" While the men were toasting, the women were in the kitchen amusing themselves about the antics of their men! Once I was at a feast in Gori, Stalin's hometown, in a palatial home opposite the Stalin museum. The father of the host had been assassinated by Stalin and yet one of his toasts as the tamada was dedicated to the "Great Stalin."

I lived in the student dorm and got to know some of the students, and went running and found a "running buddy" who was bitterly anti-Soviet, providing me with plenty of complaints about the Soviet culture of war and its consequent bureaucracy and inequalities.

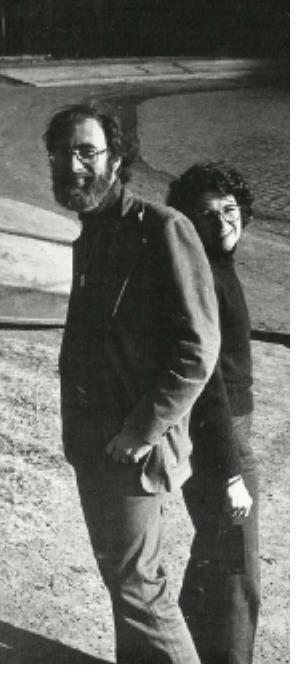

Lindsay came over with her sister to visit for several weeks and she brought a good camera for my friend Misha Nasberg, an excellent photographer. Misha repaid us by taking a day just to make photos of us in the picturesque places around Tbilisi - some of the best photos we have ever had.

Several times I came back to Georgia for brief visits, twice for scientific meetings in Gagra (1978 and 1983) and twice on vacations (in 1983 and 1984). The trips with the Georgian scientific community from Tbilisi to Gagra by train were especially memorable.

On my way back from one of my trips I decided to buy a Georgian carpet, woven in the Persian tradition. Somehow my friends got me to a huge warehouse where thousands were being stored. I was surprised at the high price, so I had them show me dozens and dozens, one after another, until they unfurled one especially beautiful rug and a mouse ran out. I looked and sure enough it had eaten a small hole in one of the corners. "I'll take it", I said, and then bargained it down to half price on that basis. It was not easy getting it through customs at the Moscow airport, but with a little bribe I managed. And it is now under my feet as I type this in my office.

While I was there in 1980 the CIA was active in trying to overthrow the Soviet Union and using American professors to do it. One of my Fulbright colleagues openly boasted that he was running guns for the CIA into Grozny for the Chechnya separatists that would later erupt into open warfare against the Soviet Union and Russia.

At the age of 18 Zura was not yet political, but I told him that he needed to appreciate the importance of politics so I arranged to go with him to see his grandmother who had taken part in the 1918 Menshevik revolution in Georgia, and asked him to learn from her about the nature of political action. Over the years I would hear from him occasionally as he helped to develop the Green Party of Georgia and then became a leading parliamentarian (see his 1989 letter and an english translation. He played a key role in the Velvet Revolution in 2003 and became the Prime Minister of the new revolutionary government of Georgia. He died in 2005 of gas poisoning which was called accidental, but which many believe was a political assassination.

|

Stages

1986-1992

Fall of Soviet Empire

1992-1997

UNESCO Culture of Peace Programme